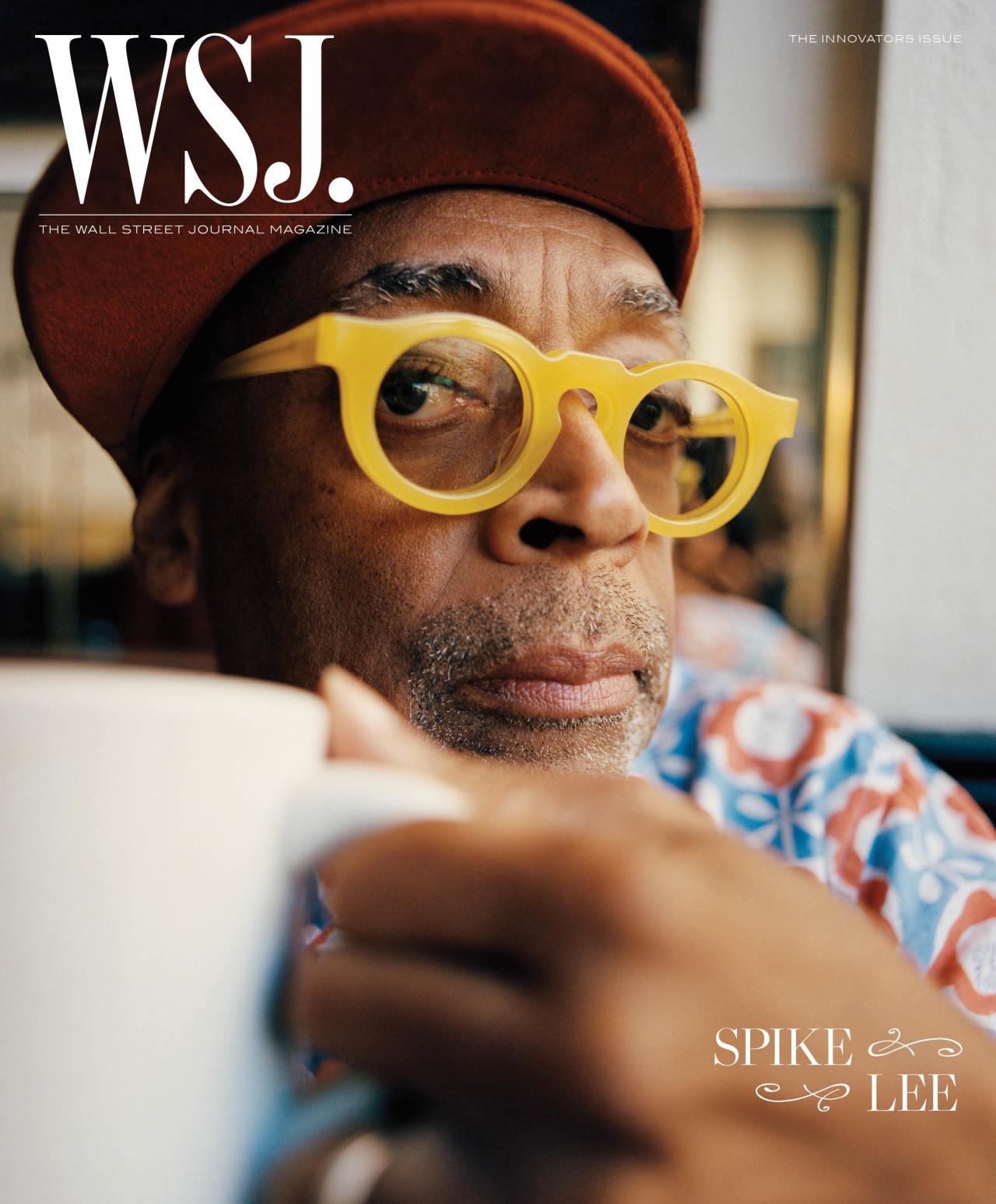

Spike Lee Sees Hollywood in Chaos. But His Legacy is Forever

Thirty six years after ‘Do the Right Thing,’ the director remains the unofficial poet of Brooklyn.

SPIKE LEE processes the world through movie titles, and on a Monday morning in Brooklyn’s Fort Greene neighborhood, there’s one that keeps coursing through his mind.

The Year of Living Dangerously.

Dangerous—because Lee, a commentator on life in America since his first feature in 1986, doesn’t quite know what to say about this moment of political violence and censorship. Or whether he should say it.

Dangerous—because Lee, whose first feature cost $175,000 strung together through the handouts of friends and family, has released a new movie co-produced by one of the world’s richest tech companies.

Dangerous—because that movie, like the industry that surrounds him, questions the encroachment of artificial intelligence into the creative process.

Dangerous—because Lee can’t walk three steps out the door without being recognized.

“This man!” an admirer yells on the neighborhood block that houses Lee’s company, 40 Acres and a Mule Filmworks. “Since School Daze.”

Lee has been famous for much of his adult life and, since a supporting role in his first movie, She’s Gotta Have It, has cultivated a personal aesthetic that, in today’s parlance, would be called a brand. On-screen, he has made movies—he calls them “joints,” another Lee signature—that have proven so provocative and influential that Lee is getting asked to explain them and himself decades after their premieres.

At 68 years old, Lee occupies a peculiar place in Hollywood. He is simultaneously early and late to trends, a proto-influencer before the smartphone made producers of us all, and also among the last of the celebrity directors to come from the film-school brigade of Scorsese, Coppola and Lucas.

On this Monday morning, Lee is dressed in chunky white Ray-Ban glasses, a baseball cap advertising the 1619 Project and a track jacket emblazoned with Tommie Smith and John Carlos, the Olympic medalists who protested racial injustice from the podium of the 1968 Summer Games in Mexico City. The facade of his office highlights the old with the new: Next to a mural of deceased cast members from his 1989 breakout, Do the Right Thing, is a poster for his latest release, Highest 2 Lowest.

Not even his building can blend.

IN 1963, Spike Lee was one member of the “first Black family in Cobble Hill.” His father, a jazz bassist who played with Woody Guthrie, Bob Dylan and members of the 1960s folk movement, had to go where the music took him, and it took the Lees to New York. Lee and his siblings grew up with family trips to jazz festivals and stories of their dad’s work friends “Bob” and “Aretha.” But when Dylan went electric at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival, Bill Lee didn’t want to go with him. He lost gig after gig with musicians who asked him to update the upright bass—refusing to do so and prompting his wife, Jacqueline Carroll, to take a job teaching to support the family of seven.

“I got to be an adult, and I understood that my father had ethics, and morally, spiritually, he could not play electric bass,” says Lee.

There’s a scene in Lee’s latest film, Highest 2 Lowest, that serves as an unlikely tribute to Lee’s father. David King, a music-industry impresario played by Denzel Washington, warns his colleagues of artificial intelligence infecting a business driven by gut instinct and human sensibility. “It’s very tricky when you’re talking about the arts,” says Lee. “You know, do machines have a heart? Do they have a soul? They don’t live and breathe.”

In his character’s admonition, Lee is staking his position as new AI-powered tools threaten to undo a system of moviemaking built on flesh-and-blood cast and crew. Lee is quick to distinguish himself from the “fuddy-duddy” types who resist progress—as a kid, he snuck Beatles albums into the house against his dad’s wishes. But the idea of machine-produced paintings or movies conceived by code gives him pause. “Gimme human beings—heart, soul,” he says. “Can you blame me? My father wouldn’t play electric bass!”

Highest 2 Lowest is Lee’s fifth film with Washington, a collaboration that began with Mo’ Better Blues and has included Malcolm X and Inside Man. The actor brought Lee the script, a reimagined take on a novel that once inspired a 1963 Akira Kurosawa film about a class divide involving a kidnapping, a businessman and a chauffeur. Lee’s take on the subject matter places the story in the contemporary music industry, where Washington is “King David,” a music executive whose son is targeted for kidnapping, but it turns out that the criminals mistakenly take the son of his driver, an ex-con played by Jeffrey Wright. Like many of Lee’s movies, it feels entirely of-the-moment, even down to a public celebration of criminality that calls to mind the embrace of Luigi Mangione, who’s been charged with killing UnitedHealthcare chief executive Brian Thompson.

The companies behind it reflect the moment, too, and not in ways Lee necessarily appreciates.

A24, the cooler-than-cool outfit behind Lady Bird and Civil War, released the movie with a limited theatrical run. Then its co-producer, Apple, premiered it on the company’s streaming service. Lee says he was caught off guard. “I was not happy,” he says. Friends texted to say they’d have to drive 50 miles to find a theater showing the film, a far cry from the 1980s when he got his start, and the multiplex drove culture.

“It’s never going back,” he says. By mid-September, only a small number of theaters were still showing Highest 2 Lowest, including an Alamo Drafthouse in Brooklyn that last year was christened the Spike Lee Cinema.

HIGHEST 2 LOWEST takes place not far from that theater, in the Olympia Dumbo, a sail-shaped condo building where Washington’s character lives in a penthouse worth nearly $20 million. It is three miles and a world away from the Brooklyn of Lee’s earlier films.

“You know what it’s called?” Lee says. “Gentrification.”

Lee has been the unofficial poet laureate of Brooklyn for nearly four decades, since Do the Right Thing introduced the world to a block of Bedford-Stuyvesant on a scorching summer day. Lee played Mookie, a pizza delivery worker who watches his community reach a boiling point with the Italian owners of a pizzeria. The movie was released 36 years ago and has themes, references and jokes that make it feel like it came out last week, including nods to the polar caps melting and Donald Trump, then a mere real estate mogul from across the bridge. The climactic confrontation reaches its peak intensity after a Black man dies in a police officer’s choke hold and Mookie heaves a garbage can through the pizzeria’s window. When the movie premiered, some theaters refused to show it, worried its on-screen riots would inspire off-screen criminality. Since then Lee has been called on to explain his characters’ actions. “No Black person’s ever asked me why Mookie threw the garbage can through the window,” he notes.

When Do the Right Thing failed to receive a nomination for best picture at the Academy Awards, presenter Kim Basinger went off script to criticize the omission. “We’ve got five great films here,” Basinger said, referring to that year’s nominees for the top Oscar. “And they’re great for one reason: They tell the truth. But there is one film missing from this list that deserves to be on it because, ironically, it might tell the biggest truth of all. And that’s Do the Right Thing.” The eventual winner of best picture, Driving Miss Daisy, about a Jewish Southerner and her Black driver, offered Lee an unwelcome sense of déjà vu in 2019, when Green Book, about a Black pianist who must be accompanied on a tour with a white driver, beat his own BlacKkKlansman.

“Every time someone’s driving someone else,” he said at the time, “I lose.”

Yet few directors have built the repertoire Lee has, with or without a best picture win: Jungle Fever, Malcolm X, Summer of Sam, 25th Hour, Da 5 Bloods. He says his 1997 documentary, 4 Little Girls, on the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, that killed four young Black churchgoers, is his greatest accomplishment, because it encouraged the FBI to continue investigating the decades-old case.

He recently screened 4 Little Girls for his class at New York University, where he teaches every Thursday. He attended film school there in the early 1980s and started drawing acclaim since his thesis—Joe’s Bed-Stuy Barbershop: We Cut Heads—made at 25 years old for $12,000. His first feature, She’s Gotta Have It, almost didn’t survive being held hostage by a film-processing laboratory that Lee owed $2,000.

The movie was financed with help from friends like Earl Smith, who handed over a $5,000 life-insurance check he’d received when his mother died. The funding allowed Lee to finish the movie and make it to the Cannes Film Festival in 1986, where it premiered. Lee’s look at a woman juggling three boyfriends earned him the festival moniker “the Black Woody Allen.” “We’re both from Brooklyn and we’re both funny,” Lee allowed at first, before the description wore on him.

It was a critical hit—and, with a box-office gross of $7 million, enormously profitable. Smith’s $5,000 donation proved a savvy investment: He owns two brownstones in Brooklyn today, Lee notes, with a peal of laughter.

Now that he’s back on campus in the professor role, class typically consists of a screening of an old movie that Lee has on his mind—A Face in the Crowd, about a TV barker who assumes dangerous political power, was one recent selection. Then he holds office hours to go over works in progress. He described himself as a tough teacher. “Half-stepping? You know, lollygagging? They get an earful,” he says.

The word “try” is banned—if a student says it, Lee lets out a squeal so loud that the teaching assistant on the other side of the wall can hear it. His inspiration comes from Yoda, whose adage “Do or do not. There is no try” serves as a constant signpost. He recently had a student say “try” five times, earning five loud squeals. “I just want my students to understand,” says Lee. “This s— is serious.”

HE’S SERIOUS, yes, but no one cracks themselves up quite like Spike Lee. A joke about fake watches—“is that a Rolex or a Nolex?”—practically has him on the floor. When he really likes the joke, he stomps his feet up and down.

A director even off set, he walks into a room and immediately adjusts the lighting before he sits down. Over the course of a three-hour conversation, totems appeared on the table before us as he referenced them: a collection of Jamel Shabazz photography called A Time Before Crack, the new biography of James Baldwin, an inscribed early copy of Kamala Harris’s new memoir. When a song popped into his head, the conversation stopped until he could find it on his iPhone, and play it in its entirety.

Lee’s movies might reflect the world, but he has perfected world-building of his own. The office in Fort Greene might be called SpikeWorld, a theme park with attractions that include:

• tributes to its creator’s obsessions (framed New York Knicks jerseys, gargantuan foreign-release posters of On the Waterfront)

• a repository of the filmmaker’s own oeuvre (gold records from He Got Game, early posters of Do the Right Thing)

• a multifloor exhibit of American Black excellence (a painting of Toni Morrison near the entrance, a voided passport of Muhammad Ali’s in the bathroom).

The other SpikeWorld remains the blocks of Bed-Stuy forever associated with Lee: in murals of the cast, or in the street signs that have announced the block as Do the Right Thing Way since 2015.

Jernysse Jackson, a grandmother of six walking back to work on Do the Right Thing Way on a Sunday in September, has lived in the area long enough to remember its pre- and post-Spike days. She remembered her friends in middle school interrupting an afternoon to let her know about a massive gathering in the streets—hordes of people yelling “Fight the power!” as they marched through the heart of Bed-Stuy, filming a music video for the Public Enemy anthem that Do the Right Thing helped make famous. “I knew it meant strong—us sticking together, helping one another,” she says.

On one corner today, Jeison Arias operates the Good Times Deli, where an oversize mural of Lee (glasses, hat, slightly stupefied expression) draws in customers and tourists. The building’s facade can be seen in Do the Right Thing around minute 27. Arias has the frame saved on his phone.

Since Arias bought the deli in 2021, he has had to stock a bodega for the dual clientele that Lee clocked nearly four decades ago. When he tried to replace a Bunn coffeepot with a fancier machine, the “old ladies” who come in each morning protested—“I want to see my coffee,” they said. But the younger renters moving in keep the cash register humming with sales of IPAs and White Claws.

Residents are quick to point out that the pizza shop that serves as the tinderbox of the film never existed—the set was built so it could be destroyed in the filming. But on a recent Sunday afternoon, the two blocks of Bed-Stuy that Lee immortalized paid an unlikely tribute, when a young woman opened the door to her brownstone, peered down the street and stepped out in bare feet. She was waiting for her dinner to arrive—four pizzas, delivered not by Mookie, but by an anonymous helmeted driver on a scooter who had sped away before she stepped back inside.

Header video: Jimmy Liu Nyeango for WSJ. Magazine; production, Counsel.

Write to Erich Schwartzel at erich.schwartzel@wsj.com

One Subscription.

Get 360° coverage—from daily headlines

to 100 year archives.

HT App & Website