With rifles and imported arms, criminals outgun Delhi-NCR cops

Delhi Police recently seized an improvised AK-47 rifle which had been assembled in the underground gun-making workshops of Bihar’s Munger district.

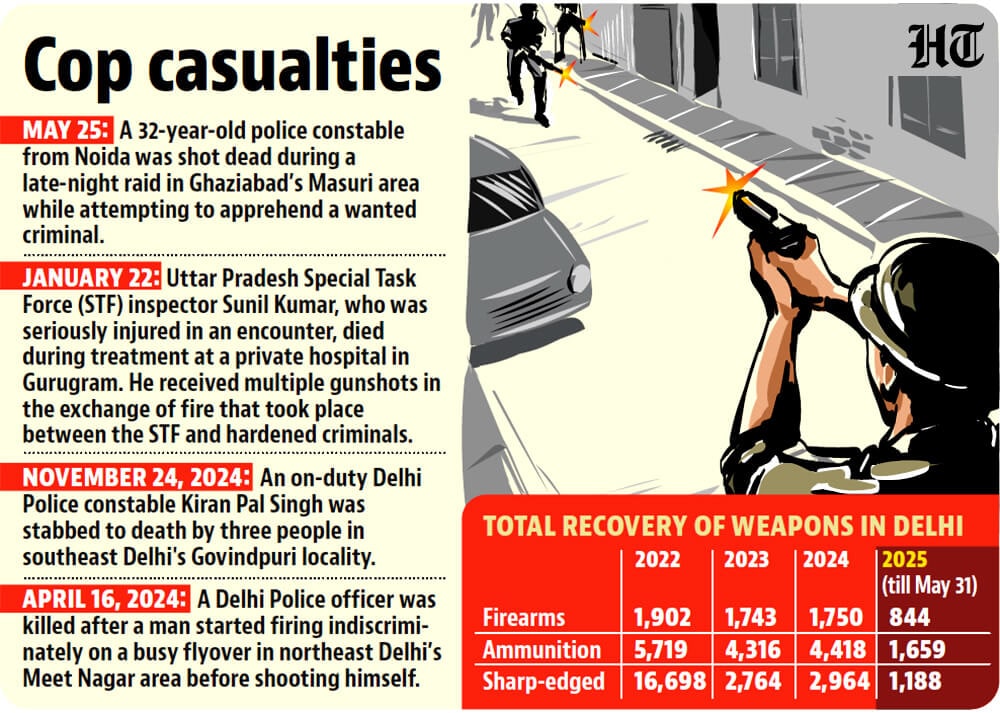

If over a dozen murders of policemen in the last two years is an indication, police personnel across the National Capital Region (NCR) are being increasingly outgunned by criminals wielding assault rifles and imported handguns, often acquired through illicit markets. While gangsters brandish high-end international handguns and assault rifles, police forces are often equipped with little more than aging 9mm pistols, outdated rifles, and often even just batons.

Also Read: Delhi’s gun underworld">Rajasthan’s rising role in Delhi’s gun underworld

Criminals, increasingly resourceful and mobile, benefit from a burgeoning black market in arms. In a recent case, Delhi Police seized an improvised AK-47 rifle with 30 live cartridges. The weapon, assembled in the underground gun-making workshops of Bihar’s Munger district, was meant to be sold for just ₹2.4 lakh. The accused, a man named Kapil Kumar, told police that he acquired the gun from a property dealer and was allegedly supplying it to gangs operating in Uttar Pradesh and Haryana.

The illegal arms industry has long flourished in India’s hinterlands. Delhi Police’s special commissioner of police (crime) Devesh Chandra Srivastava said that after Bihar’s Munger district, Western UP’s Bulandshahr and Madhya Pradesh’s Mhou area, Rajasthan’s Deeg area has now become a hub for manufacturing knock-offs of sophisticated weapons.

“The process is astonishingly informal. Crude lathes and welding equipment in tiny backyard workshops churn out imitations of AK-47s and other semi-automatic firearms with alarming efficiency. Despite frequent raids, the ecosystem has proved resilient. Intelligence inputs suggest that weapons produced in Munger and similar areas are increasingly ending up in urban centres like Delhi, feeding a growing appetite among organised crime syndicates,” he said.

In a major crackdown in May this year, Delhi Police busted an illegal arms manufacturing and supply syndicate operating from Deeg, arresting five people over a three-day operation. The gang allegedly supplied weapons to criminals in Delhi-NCR, including the Vikas Lagarpuria gang.

Joint CP (Crime) Surender Kumar said that the accused—Harvinder Singh, Sonu Singh, Mohammad Mubin, Sher Mohmad alias Sheru, and Mohammad Juber—were held after raids in four Deeg villages.

“Police recovered 11 illegal firearms, including a rifle and 10 pistols, along with 17 live cartridges and weapon-making equipment. The probe began after the March 4 arrest of gangster Rohit Gahlot, who named Juber’s Deeg-based network. The gang operated from forested areas and was ready to open fire on police during the raids. Mubin, trained in arms-making since 2013, sold pistols for up to ₹12,000. Harvinder and his cousin Sonu resold weapons to Delhi gangs, with the former building direct links with criminals,” he said.

Against this backdrop, the state of police preparedness in NCR appears dangerously anachronistic. According to data compiled by senior police officials, only a handful of police stations in Delhi, Uttar Pradesh, and Haryana can even claim to possess AK-47 rifles, let alone officers trained to use them.

A retired special commissioner of Delhi Police said that while both weapons are lethal, their real-life impact is very different. “A 9mm pistol is a short-range sidearm, typically used for personal defence or in close encounters, firing smaller cartridges with limited stopping power beyond a few dozen metres. In contrast, an assault rifle such as the AK-47 is a high-calibre automatic weapon designed for battlefield conditions. It can fire rapidly over several hundred metres, penetrate walls or vehicles, and cause mass casualties in crowded places. This stark difference in range, firepower and destructive potential is why the recovery of an assault rifle is treated by law enforcement as far more alarming than the seizure of handguns,” he said, asking not to be named.

Former joint commissioner of Delhi Police BK Singh said that the standard firearm for most policemen remains the 9mm pistol.

“The contrast is stark when these officers face adversaries with more powerful and accurate automatic weapons. This structural imbalance has grave implications for on-ground law enforcement. In theory, the Quick Response Teams (QRTs) are supposed to offer a muscular reply in crisis situations. But in practice, the reality is bleaker. The drivers of QRT vehicles are often private hires with no formal police training, and many vehicles lack basic bullet-proofing. In sensitive zones, delays in deployment can be fatal. If we have a Mumbai-style terrorist attack situation in Delhi, it will be interesting to see who drives into the fire first—the civilian driver or the policeman in the back,” he said.

The Union ministry of home affairs has repeatedly called for modernisation of the police force, with annual allocations for arms procurement, training, and equipment upgrades. Yet implementation is patchy. According to the Bureau of Police Research and Development, India has one of the lowest police-to-population ratios among G20 nations—just 152 officers per 100,000 people, far below the United Nations’ recommended 222. More worryingly, there is a lopsided focus on ceremonial or riot control gear rather than actual combat-readiness. A large share of equipment funds are funnelled into shields, batons, and surveillance cameras, while frontline weapons remain outdated.

“The discrepancy between criminal sophistication and police preparedness is not limited to weapons. It extends to communication, mobility, and tactical response. Gangs often use encrypted messaging platforms, GPS trackers, and drones for surveillance and planning. Police departments, still reliant on wireless sets and handwritten logs, lag behind. The result is a force that reacts rather than anticipates—a serious handicap in the cat-and-mouse game of modern crime-fighting,” added Singh.

There are, of course, exceptions. A few elite units, such as Delhi’s Special Cell or Uttar Pradesh’s Anti-Terrorist Squad, are better trained and better equipped. But these units are small, centrally based, and not deployed for routine crime control. The vast majority of India’s 1.7 million police personnel operate in conditions that compromise both their safety and efficacy.

The wider issue is not merely operational -- it is political. Police reforms in India have been stalled for decades, caught in the crosshairs of bureaucratic inertia and political interference. The Supreme Court’s directives from the Prakash Singh judgment in 2006, which called for greater autonomy and depoliticisation of police forces, remain largely unimplemented across states. The continued use of colonial-era laws and the over-centralisation of police command structures only deepen the inefficiencies.

In an era of urban terror threats, interstate crime networks, and sophisticated trafficking rings, India’s frontline police are dangerously ill-equipped. Without meaningful reforms—both in hardware and institutional culture—the imbalance between police batons and criminal AK-47s will persist. And in that unequal fight, it is not only officers who pay the price. Society does too.

Stay updated with all top Cities including, Bengaluru, Delhi, Mumbai and more across India. Stay informed on the latest happenings in World News along with Delhi Election 2025 and Delhi Election Result 2025 Live, New Delhi Election Result Live, Kalkaji Election Result Live at Hindustan Times.

Stay updated with all top Cities including, Bengaluru, Delhi, Mumbai and more across India. Stay informed on the latest happenings in World News along with Delhi Election 2025 and Delhi Election Result 2025 Live, New Delhi Election Result Live, Kalkaji Election Result Live at Hindustan Times.

One Subscription.

Get 360° coverage—from daily headlines

to 100 year archives.

HT App & Website