Why Workers in Their 40s Are Going Back to School

It’s tough to go back to school in your 40s. But with layoffs, stagnant pay and inroads by artificial intelligence, many of those nearing midlife are heading back to classrooms and trade schools.

Some are making radical career changes, going from chef to software engineer. Others are getting higher degrees to stand out from peers as qualification standards intensify. Some who skipped college after high school return to the classroom because they can’t get top jobs without degrees.

Returning to school isn’t easy. Those in their 40s often have to juggle work, family and academics. They take on new debt when peers are entering peak-earning years. The average cost of in-state public college is about $30,000 a year and much more for private nonprofit schools.

For many, it’s worth it. People are living longer and aren’t retiring at 65.

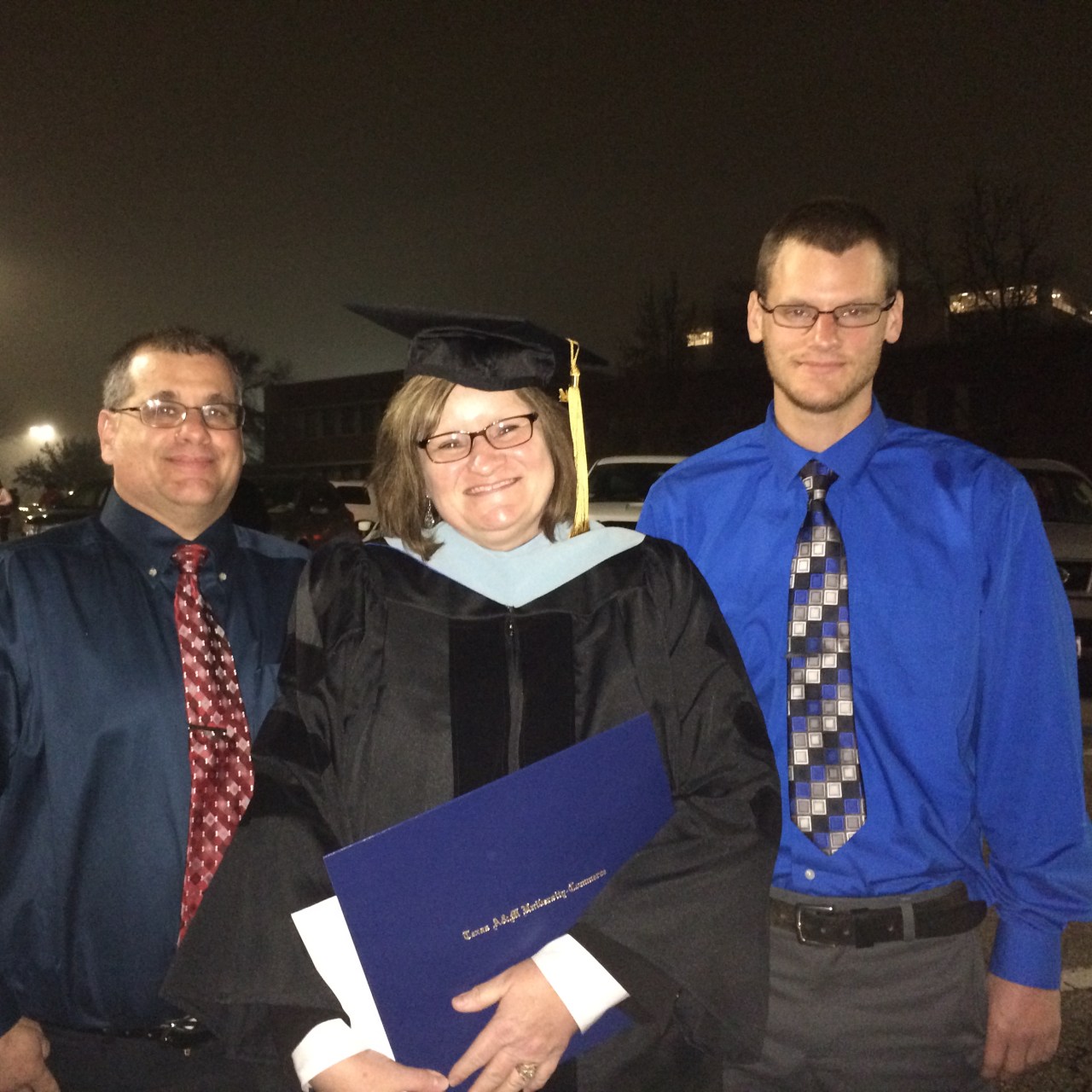

Cindy Woody earned her master’s at 41 and completed her doctorate at 47. “I’m a good investment,” says Woody, an assistant professor of educational leadership at the University of Texas at Tyler.

Longevity, she says, runs in her family. Her great grandmother lived to almost 100. Woody worked full time while going to school, quit watching TV and handed off housework to family members while she attended in-person classes at night and on Saturday. She wrote papers between 3 a.m. and 6 a.m. or on Sunday afternoons.

More than 1 million people in their 40s are enrolled in undergraduate or graduate programs, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. Many are looking to make more money in the white-collar world and have greater job security, even at a time when many younger people are questioning the value of a college degree.

Skilled trade and apprenticeship programs, which can cost as little as $3,000 a year, are seeing an influx, too, in part because those jobs are seen as less vulnerable to automation and artificial intelligence. Leaky pipes need plumbers.

One fourth of the 108 students enrolled in a Pennsylvania job-training program are in their 40s, learning plumbing, carpentry, construction, healthcare and other skills. Many have either lost jobs or want better pay.

“This year we’ve seen more layoffs and closures,” says Erica Mulberger, executive director of Advance Central PA, a nonprofit local workforce development board.

One student, Victoria Miner, 48, enrolled in a four-year butcher apprenticeship program, learning to process meat products according to USDA standards. Miner, who raises cattle, felt she needed the training to get taken seriously in a male-dominated industry.

Her certification led to a job offer as a USDA inspector, which is less physically demanding than butchering and can extend her career. “At this stage in life, using my brain instead of brawn is a better fit for me,” says Miner.

Degrees and certificates lend credibility. Kevin Korenthal skipped college after high school but worked his way up to leadership roles in the nonprofit world. Top executive positions, though, remained elusive.

“It’s really hard to get those roles without a degree, no matter how capable you are,” says Korenthal. He returned to school in his early 40s for an associate degree in digital media, followed by certification for association executives. He did both while working full time and raising two kids.

Afterward, he found an online program at Indiana University designed specifically for late-life learning and got his bachelor’s in nonprofit leadership. Now 53, Korenthal is executive director of the National Association of Park Foundations.

Cost is often an obstacle, but near-midlife students find ways to manage.

Melissa Harkin, a successful freelance translator, already had master’s and law degrees from her native Brazil. Melissa Harkin, a successful freelance translator, already had master’s and law degrees from her native Brazil. She decided she needed a diploma from a university in the U.S. or Europe to get hired at an American company.

After discovering U.S. master’s programs in linguistics and translation cost more than $50,000, she found a similar program at the University of Birmingham in England for $22,000. While taking classes remotely, she also took an eight-week course at Harvard for a higher-education teaching certificate for about $3,000.

At one point, Harkin, 45, realized she hadn’t left her apartment in two months. She missed her son’s swimming and jujitsu lessons.

“At 40, with family, if you put the time in to do it and do it right, it means missing out on other things,” says Harkin, who works at Innodata, designing training and assessment materials for large-language model artificial-intelligence projects. She calls the two education programs her best investment in the last three years.

Others want a new career because the profession they loved in their 20s and 30s didn’t offer the benefits, pay and stability they needed.

LaToya Hall, a chef for an upscale catering company, was on her feet all day, working unpredictable hours and moving heavy food trays for weddings and bar mitzvahs. During a camping trip, she decided to go back to school. By the time she arrived home, Hall had applied for an 18-month software engineering and web-development associate degree program at New England Institute of Technology.

“I knew I needed a change and felt ready,” says Hall, a 40-year-old single mother of two. She sold her car to save money and took three buses to get to classes, leaving at 5:30 a.m. to make her 7:45 a.m. class.

Hall landed an internship while in school, which turned into a full-time job with AAA as a digital-content producer. She received grants and scholarships, but has about $40,000 in loans from her culinary school and the associate degree.

“I plan to return at some point for my bachelor’s degree,” she says.

Write to Clare Ansberry at clare.ansberry@wsj.com

One Subscription.

Get 360° coverage—from daily headlines

to 100 year archives.

HT App & Website

E-Paper

E-Paper