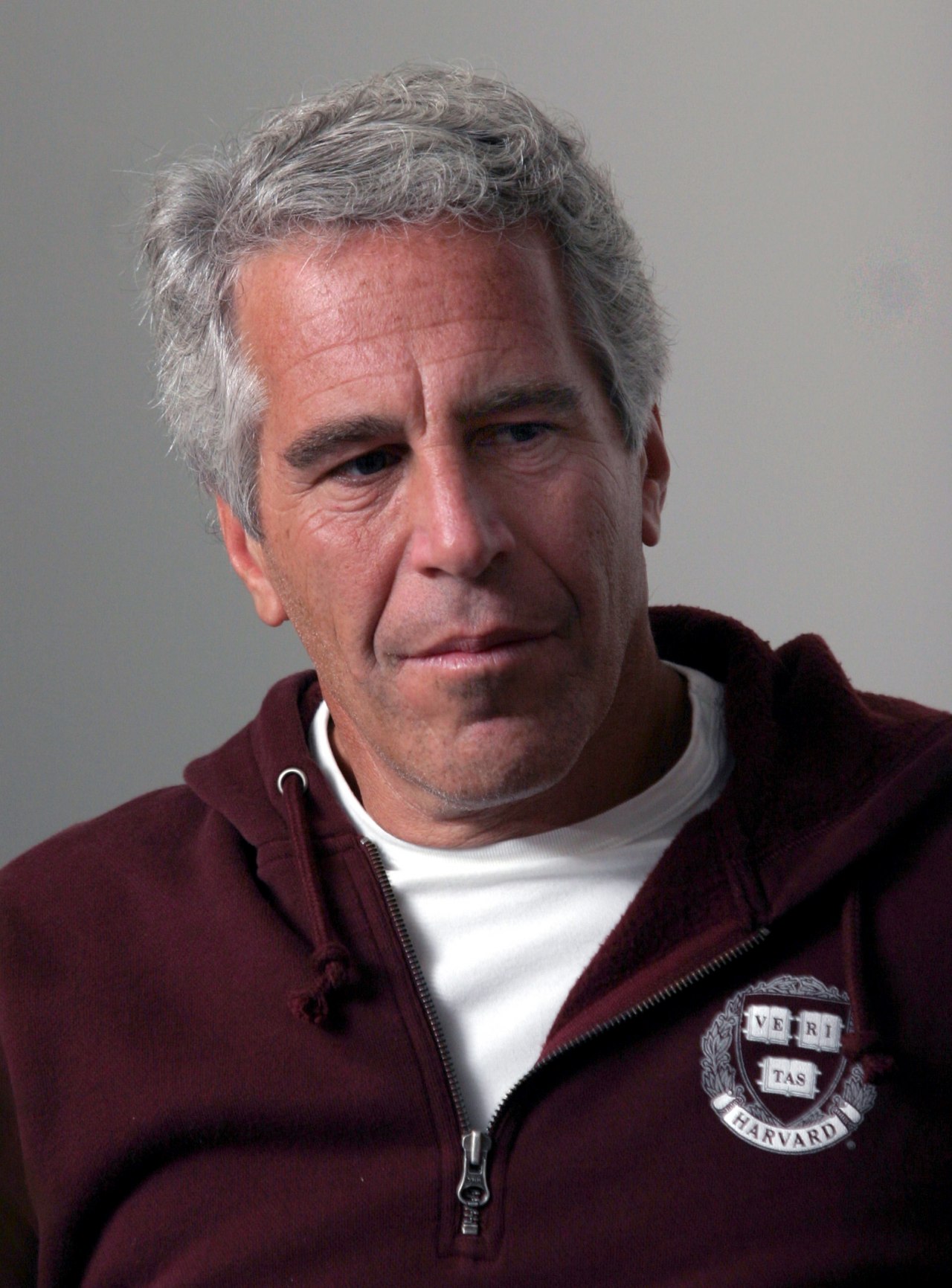

How Larry Summers’s Power Delayed the Reckoning Over His Epstein Ties

The former Treasury Secretary and Harvard president’s enormous network and clout kept him immune from past Jeffrey Epstein revelations.

Last November, a collection of business, academic and political luminaries made a pilgrimage to a wood-paneled conference room at Harvard University. They were there to pay tribute to Lawrence Summers, the former Treasury Secretary and university president, and one of the foremost economists of his era.

During a day-long event to mark his 70th birthday, Summers basked in praise from guests including former Meta chief operating officer Sheryl Sandberg and Gene Sperling, who directed the National Economic Council for Presidents Clinton and Obama.

This week, a chastened Summers found himself in different circumstances: standing in the well of a Harvard lecture hall, asking his students’ forgiveness as his professional life was unraveling.

“Some of you will have seen my statement of regret, expressing my shame with respect to what I did in communication with Mr. Epstein,” Summers said, according to a video taken by an attendee and posted to social media. “But I think it’s very important that I fulfill my teaching obligations.”

The question now is: Why did it take so long for Summers’s ties to Epstein to wound his highflying career?

This wasn’t the first time Summers was compelled to express regret to the Harvard community for his extensive ties to the late sex offender, Jeffrey Epstein. Over the years Summers had flown on Epstein’s private plane, according to flight logs. The two had then maintained a personal relationship long after Epstein’s 2008 plea to underage prostitution charges in Florida prompted Harvard to refuse his donations. Summers courted him to help fund an online poetry project being developed by his wife, now an emerita Harvard literature professor.

Those prior revelations never appeared to impede the career of a giant in both academic and policy worlds—one whose blessing could be career-making for young acolytes and whose gravitas and extensive professional network made him indispensable for organizations in moments of crisis. He was barely mentioned in a 2020 report Harvard published detailing its institutional ties to Epstein, who was arrested on sex trafficking charges the previous year. And in 2023—months after The Wall Street Journal reported new details of Summers’s correspondence with Epstein—he won a plum assignment: an appointment to a new board at OpenAI, the artificial intelligence company behind ChatGPT.

“He’s an extremely powerful man with an enormous network of people who have learned from him, been mentored by him. He’s powerful in D.C., powerful at Harvard. That counts for a lot, and that explains a lot,” said Susan Dynarski, a well-known Harvard economist affiliated with its Graduate School of Education.

But this time is different. The immediate cause of Summers’s undoing was the release of a passel of messages in which he asked advice from his friend Epstein on “getting horizontal” with a woman he was pursuing.

The messages, sent in 2018 and 2019—and up until the day before Epstein’s arrest—were needles in a roughly 20,000-page haystack of Epstein documents released by a House committee last week. They offer a glimpse into a more sordid side of the eminent economist, agonizing about how he might leverage a professional relationship into a romantic one. They reveal the intimacy of Summers’s relationship with Epstein, who described himself as a “wing man” for the economist, even as the scale of Epstein’s crimes against young women was becoming widely known.

“She’s already beginning to sound needy :) nice,” Epstein noted about Summers’s object of interest in a November 2018 message. In others, they appeared to refer to the woman Summers was attracted to by a code name: “peril.”

On Monday, Summers issued a more fulsome apology. “I am deeply ashamed of my actions and recognize the pain they have caused,” he said. “I take full responsibility for my misguided decision to continue communicating with Mr. Epstein.”

He said he would step back from public commitments “as one part of my broader effort to rebuild trust and repair relationships with the people closest to me.”

But institutions were soon rushing to cut professional ties with Summers. He was out at organizations including the New York Times, where he had been a contributing opinion writer, the Center for American Progress think tank, where he was helping to formulate a new slate of Democratic economic policies to rejuvenate the party, an advisory board at the bank Santander, Bloomberg TV, where he was a paid contributor, and the Yale Budget Lab.

By Wednesday morning, Summers had resigned his seat on the OpenAI board. Then Harvard—a mainstay in his life and career—announced it would take a fresh look at his and other faculty members’ ties to Epstein. By evening, he would take leave from his teaching duties and post as co-director of a Harvard Kennedy School academic center, too.

Summers’s fall is a reminder of the Epstein saga’s potency six years after the man was found hanged to death in a New York jail cell while awaiting trial on sex trafficking charges. The coroner ruled it a suicide.

Seemingly from the grave, Epstein is still provoking ructions in President Trump’s MAGA coalition while costing several powerful men their careers and reputations. There is likely more to come: Trump on Wednesday night signed legislation ordering the Justice Department to release its vast store of Epstein-related materials.

Yet Summers’s travails are also uniquely his own. The flip side of his enormous intellect, say critics, is a towering arrogance that alienated many over the years. The smartest guy in the room could also be strangely inept at reading the room.

New York Times columnist Maureen Dowd said in a 2013 piece that she observed him once yawn, check his watch and walk away while then-Vice President Biden spoke to a small group at a holiday party. She said Summers was “not exactly socialized” and called him “imperious.”

In 2005, Summers stoked outrage when he suggested at a conference that there may be fewer women than men in the sciences because they had less aptitude. He later insisted he’d been misunderstood, saying in a letter to the Harvard community, “I deeply regret the impact of my comments and apologize for not having weighed them more carefully.” But the furor grew, especially among a contingent of Harvard faculty, and he resigned as president the following year.

More recently, Summers angered some colleagues in the tumultuous period that followed Hamas’s October 7th attack on Israel. Pro-Palestine protests erupted on campus, along with complaints of widespread antisemitism. Summers was an early and public critic of how Harvard’s first Black woman president, Claudine Gay, handled the situation. Gay resigned early last year, in part after pressure mounted over her response to the protests.

The political ground had shifted at Harvard since Summers’s presidency. A centrist Democrat who came to prominence in the Clinton era and was a staunch supporter of Israel and critic of “wokeness” found himself on an increasingly left-wing campus.

His critics are now rejoicing.

One economist messaged a Journal reporter late Wednesday night with an emoji showing celebratory party poppers.

His comeuppance was validating for women economists, many of whom have suffered in a field that long celebrated brainy men. In a statement this week, a women’s committee at the American Economic Association condemned Summers and noted: “While abuse of power in the economics profession is not new, rarely has the intent behind such abuse been so clearly stated.”

Claudia Sahm, a former Federal Reserve economist who blasted Summers and others for sexism in a widely shared and highly critical 2020 blog post, sounded vindicated. “Okay, so maybe I wasn’t too mean to him…” she crowed on social media after the emails were made public last week.

Laurence Kotlikoff, a Boston University economist, has known Summers since graduate school and coauthored one of the first papers Summers published in an academic journal. On Tuesday, he declared his one-time collaborator “not fit to continue service as a professor at Harvard.”

“Character matters. It matters more than academic merit, power posts, and financial connections,” Kotlikoff wrote in a Substack post. “He was the smartest guy in the room. But his ego always trumped his IQ. It’s now done so in the worst possible way.”

‘Larry understood’

Smarts have never been in question for Summers, who counts two Nobel Prize-winning uncles—Paul Samuelson and Kenneth Arrow. He received his undergraduate degree from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and his Ph.D. from Harvard. In 1983, according to a biography for Summers on Harvard’s website, he became one of the youngest people in modern history to be offered tenure at the university. He won the John Bates Clark Medal, the award given to an extraordinary American economist under age 40 that has often been a precursor to a Nobel.

Summers gained wider acclaim for his handling of the 1998 emerging markets crisis as Clinton’s Deputy Treasury Secretary. He was featured alongside Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin and Federal Reserve Chair Alan Greenspan on a Time magazine cover in early 1999 in which the trio were dubbed “the committee to save the world.”

In an Instagram post last year, upon Summers’s birthday, Sandberg recalled meeting him when she was a 20-year-old Harvard student and the impact he would have on her life—and many others.

“I am one of many who to this day think of themselves as ‘Larry Summers’ student,’” Sandberg wrote, noting how he had advised on her thesis, then hired her as a research assistant at the World Bank, and later as his chief of staff at Treasury. She lauded his support for girls’ education in the developing world, as well as his personal loyalty: “Larry understood that when people were up, everyone called. But when people were down, few did. Larry reached out to people when it was hard.”

‘Epstein ties’

Summers was appointed Harvard’s 27th president in 2001, at a time when Epstein—a college dropout and onetime high school math teacher—was becoming a boldfaced name in Manhattan society, known as a shrewd, if mysterious, financier and generous patron of academia.

According to Harvard’s 2020 report on ties between Epstein and the university, compiled with the help of law firm Foley Hoag, Epstein contributed $9.17 million to the university from 1998 until 2008, when his conviction on prostitution charges prompted the administration to officially shun him. The biggest gift was $6.5 million he pledged in 2003—while Summers was president—to establish the Program for Evolutionary Dynamics. (In one of his characteristic exaggerations, Epstein would later claim he had given $35 million for the project).

In its early days, the program’s website stated that it had been founded “by Harvard University President Lawrence H. Summers following an imaginative proposal” by Epstein and an academic.

The PED gave Epstein a campus office, where he would meet—often on weekends—with top researchers and government officials. According to Harvard’s review, he visited more than 40 times between 2010 and 2018.

Summers also sought Epstein’s help for a more personal philanthropy project: an educational venture that his wife, Elisa New, was developing. “I need small scale philanthropy advice. My life will be better if i raise $1m for Lisa,” Summers said in an email to Epstein in April 2014. Two years later, a nonprofit connected to Epstein made a $110,000 donation to New’s nonprofit.

New’s nonprofit later made a contribution “exceeding the amount received, to a group working against sex trafficking,” a spokeswoman later said.

In the ensuing years, Summers would remain in regular contact with Epstein. “How is life among the lucrative and louche?” he asked in October 2017, in an email included in the recently released House cache of documents.

President Trump, whose 2016 election victory shocked the establishment, was a frequent subject of banter. “Is trump getting crazier as many of my pals think or is it steady crazy,” Summers asked his friend in a November 2018 email. Epstein called the president “borderline insane” the following month.

Around that time, their usual exchanges about White House gossip, geopolitics and financial markets were interspersed with discussion of a particular woman, a Chinese economist then in her late 30s with whom Summers sought a romantic relationship.

Based on emails forwarded by Summers to Epstein in 2018, the woman appears to be Keyu Jin, a Harvard-trained economist whose father, Jin Liqun, was the founding president of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and a former vice minister of finance in Beijing.

Jin Liqun wasn’t immediately available for comment. Keyu Jin didn’t respond to a request for comment.

She came to study in New York during high school before earning degrees at Harvard. A longtime lecturer at the London School of Economics and, more recently, the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, she is known as an articulate and effective promoter to western audiences of China’s state-led economic policy.

Summers’s emails suggest he was smitten with her, and agonizing over whether to pursue an affair—and, if so, how to go about it. “Think for now I’m going nowhere with her except economics mentor. I think I’m right now in the seen very warmly in rearview mirror category,” he wrote Epstein from a conference at 10:53 p.m. on Friday, Nov. 30, 2018. “She did not want to have a drink cuz she was ‘tired.’ I left the hotel lobby somewhat abruptly. When I’m reflective, I think I’m dodging a bullet.”

The next morning, he was still fretting, telling his confidant: “I sent a note just asking her to txt when she was up cuz I had something brief to say to her. Didn’t want to push cuz she takes her 930 presentation here very seriously. Better after her talk.”

Then Summers asked: “Am I thanking her or being sorry re my being married. I think the former.“

Epstein concurred, replying: “thanking her for fortitude in dealing with what has obvioulsy [sic] been a tough situation. and acknowlegin [sic] both how difficult it has been coupled with your inate [sic] insensitivty. [sic] and apologizing for not fully recogbnizing [sic] how difficult it has been.”

By 10:29 a.m., Summers appeared infatuated. “Game day at conference she was extremely good,” he wrote Epstein in an update. “Smart Assertive and clear Gorgeous. I’m fucked.”

Write to Joshua Chaffin at joshua.chaffin@wsj.com, Melissa Korn at Melissa.Korn@wsj.com and Justin Lahart at Justin.Lahart@wsj.com

One Subscription.

Get 360° coverage—from daily headlines

to 100 year archives.

HT App & Website

E-Paper

E-Paper