Why Taking Venezuela’s Oil Could Actually Lift Its Fortunes

Economists say the U.S. selling Venezuela’s backlogged crude supply could help bring the country out of the shadows.

President Trump’s surprise announcement that the U.S. would take millions of barrels of Venezuelan crude could be an economic boon for the battered South American nation—if Washington and Caracas can maintain their nascent detente, U.S. officials and economists said.

That might be a big if, but economists said restoring a trade link with the U.S. would generate badly needed cash for a country dependent on importing food and basic goods. Trump said in a Truth Social post Tuesday that Venezuela would turn over to the U.S. 30 million to 50 million barrels of oil, which would be sold at market price. Trump said he would personally control the proceeds “to ensure it is used to benefit the people of Venezuela and the United States.”

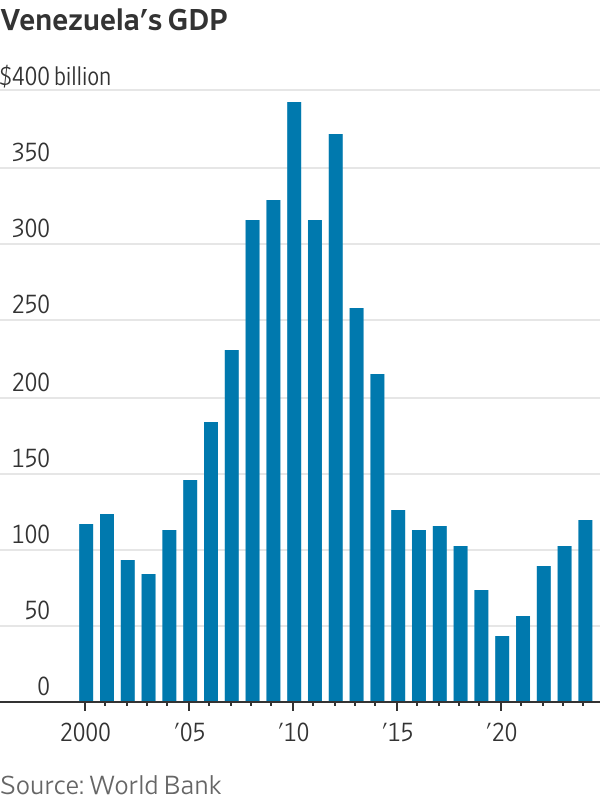

Venezuela currently has more than 30 million barrels of backlogged crude supplies in storage that it hasn’t been able to sell because of a partial U.S. embargo. Selling that oil—at market prices rather than the steep discount Venezuela must take on the black market—could help jump-start an economy that has nosedived over the past decade.

“It sounds contradictory,” said Alejandro Grisanti, president of the Caracas, Venezuela-based business consulting firm Ecoanalitica. “But if we’re able to achieve some kind of understanding between the U.S. and Venezuela, we can easily move from a strong negative decline to positive growth.”

The price of Venezuelan government bonds soared this week to levels unseen since the regime defaulted on its sovereign debt in 2017. That is a sign, Grisanti said, that investors believe the country could reincorporate into the global financial system and eventually settle some $160 billion in outstanding debts.

Much of it depends on a tenuous political detente between the Venezuelan government and Trump, who ordered the arrest of strongman Nicolás Maduro in a U.S. military raid early Saturday. The autocrat, who ruled the country since 2013, was succeeded by his deputy, Delcy Rodriguez, long Venezuela’s de facto economic overlord, who Trump said would work with the U.S. or else face the wrath of American justice.

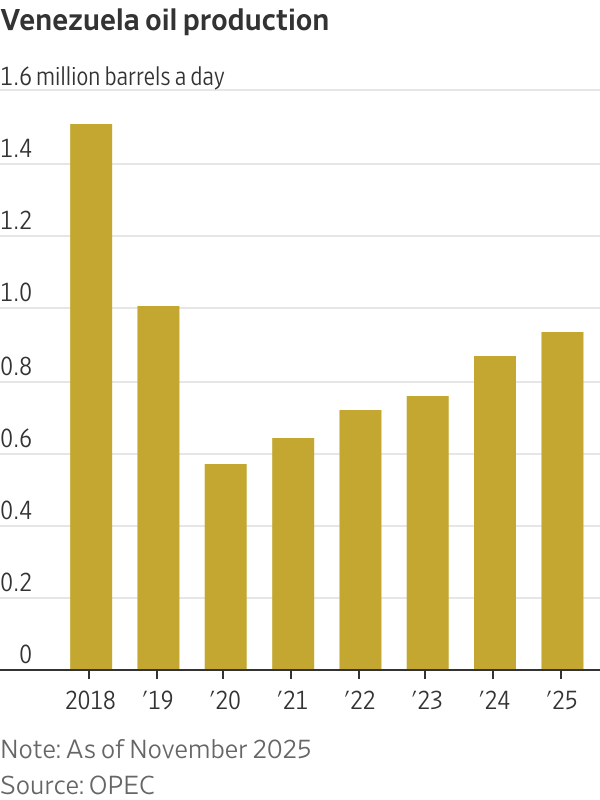

If the U.S. doesn’t follow through and pay Venezuela back, it would be catastrophic for a country projected to run 700% inflation this year. The U.S. would be taking as much as 15% of Venezuela’s current annual crude production. Without financial compensation from the U.S. for that much oil, the heavily import-dependent country would face widespread food shortages, as it has in the past.

Some economists said U.S. plans to stabilize the Venezuelan economy are doomed to fail without elections and stable democratic institutions. Ricardo Hausmann, a Venezuelan economist at Harvard Kennedy School, said companies would need confidence in the legal system to invest billions of dollars.

“There is no recovery of the oil industry in this context,” said Hausmann, a former Venezuelan planning minister. “I can perfectly see the situation becoming worse.”

Secretary of State Marco Rubio said the oil transfer is just the first phase in a three-pronged plan that the U.S. is launching for Venezuela, a stabilization step to guarantee the hard-currency income that the local economy largely relies on to import food and medicine for its 28 million people.

Under the plan, the U.S. will also ensure that Venezuela’s oil reserves—among the world’s largest—will be accessible to foreign energy companies. The third phase involves shepherding a reconciliation program that would restore political rights and free political prisoners in Venezuela.

“We feel we are moving forward in a very positive way,” Rubio said.

U.S. Energy Secretary Chris Wright said at a Goldman Sachs energy conference Wednesday that the U.S. would sell the oil on the market. The money will be deposited into accounts controlled by the U.S. government, before it can pass back to Venezuela, Wright said, without giving more details.

“Let the oil flow,” said Wright. “This should be a wealthy, prosperous and peaceful energy powerhouse.”

To be sure, Venezuela is doing this without much choice in the matter, as Trump says he is running the country now. Much depends on Rodriguez, who may be hard-pressed to please Trump and maintain unity between the various factions of the regime Maduro left behind.

Rodriguez will have little time to turn things around because Venezuela’s needs are so extreme, said Evanan Romero, a former deputy oil minister.

“Some people talk about a 10-year recovery program, but we can’t wait,” said Romero. “If this doesn’t happen in a few years, everyone’s going to be dead.”

Venezuelan state oil company Petróleos de Venezuela said negotiations with the U.S. were under way and terms of the trade would be similar to those with Chevron and other foreign companies. The company called it “a strictly commercial transaction, with the criteria of legality, transparency and benefit for both sides.”

By lifting oil from Venezuela, Washington would help relieve a major bottleneck. With its oil storage nearly full, and the U.S. embargo blocking most exports, fear had spread that Venezuela would have to close oil wells, a costly and risky move. The country had only recently, with great effort, stabilized its output at around a million barrels a day—up from a low of around 500,000 barrels when U.S. sanctions first hit in 2020 but well below the 3 million barrels that the country pumped two decades ago.

Restoring trade with the U.S. market also means Venezuela can reap full price for its tar-like heavy crude. In recent years, the country has been selling at steep discounts on the black market because it moved the commodity through a ghost fleet of sanctioned tankers that skirted U.S. sanctions and transported oil to Asian buyers that paid Venezuela in cryptocurrencies. A chunk of Venezuela’s shipments to China, its largest buyer, generated no cash at all because they went to settle old debts to Beijing.

The Trump team’s announcement has also fueled speculation that the U.S. could roll back the complex web of financial sanctions it has placed on Venezuela, which could allow for more investment to flow in. Trump is meeting with oil-company executives on Friday.

With a range of repairs and investments, Venezuela’s oil industry has the potential to eventually increase production back above 3 million barrels a day, said Clayton Seigle at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington think tank. That is roughly a third of Saudi Arabia’s current output.

With investments of a few billion dollars over some 18 months, Venezuela could increase current output by some 50%, said Seigle. But to get above 2 million barrels a day, tens of billions of dollars would be needed for repairs and new builds that could take six years or more, he said.

Venezuela needs dozens of rigs and what are called upgraders—specialized facilities that remove carbon and add hydrogen, as well as major improvements to its power grid.

But none of that is possible without political stability, Seigle said. “There’s good reason to doubt the outlook for political stability in Caracas, as governance and transition plans are ambiguous at best.”

On the ground in Venezuela, there were signs that citizens weren’t celebrating just yet and were bracing for shortages of greenbacks in the economy. On Binance, the crypto exchange where many Venezuelans trade the beleaguered local bolivar currency, one U.S. dollar fetched more than 800 bolivars, compared with the central bank’s official rate of 308.

“There is a big asymmetry between what the international investor world thinks and what the local businessman perceives,” said Grisanti of Ecoanalitica.

Rodriguez, who was sworn in Monday as Venezuela’s acting president, had overseen an economic liberalization program over the past several years, whereby Venezuela dismantled its state-planned model and cut generous welfare and social spending. It also scaled down price and capital controls that once banned trading of the U.S. dollar.

The loosened control helped spur a subtle stabilization of the economy, which outpaced much of the region with 6.5% growth in 2025, according to the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean.

Still, three in five Venezuelans said they had difficulties affording enough food last year, according to a study by Gallup published Thursday. Merely 19% of adults reported being employed full time, one of the lowest rates in Latin America.

Write to Kejal Vyas at kejal.vyas@wsj.com and Samantha Pearson at samantha.pearson@wsj.com

One Subscription.

Get 360° coverage—from daily headlines

to 100 year archives.

HT App & Website

E-Paper

E-Paper